Businesses need to retain loyal customers to grow.

Customer loyalty should be guided by your company's values and commitment to meeting customers' expectations. You need to earn your customers' trust so that they stay to support you even if the market declines over time. Not to mention that having 5% of your customer base as repeat customers enables your business to grow by up to 95%!

So when promoters spread the word, your growth possibilities become endless. Calculating the Net Promoter Score (NPS) helps you understand the sentiment around your brand:

In this article, you will learn:

- How to calculate an NPS score.

- What are the NPS survey best practices––including survey questions you should ask to get reliable insights.

So, let's begin!

What's the Net Promoter Score (NPS)?

Let's remember how Wikipedia describes NPS.

Net Promoter or Net Promoter Score (NPS) is a widely used market research metric used to measure customer loyalty toward a brand, product, or service.

It typically takes the form of a single NPS survey question asking respondents to rate the likelihood that they would recommend a company, product, or service to a friend or colleague. The NPS is a proprietary instrument developed by Fred Reichheld, who owns the registered NPS trademark in conjunction with Bain & Company and Satmetrix. Its popularity and broad use have been attributed to its simplicity and transparent methodology (source: Wikipedia).

And the NPS survey lets you calculate it.

How to calculate NPS?

The NPS calculation is a popular CX metric. It helps track the company's customer experience. It's the best way of measuring customer experience at scale. Plus, you don't need to be a mathematician to understand and use it. To find out how to calculate the NPS, let's start with the basics.

Net Promoter Score calculation formula

Calculating NPS is simple. It starts with one scale-based question you usually ask your focus group in an email survey.

How likely are you to recommend our company to a friend or colleague?

- Collect the NPS survey results.

- Subtract the number of detractors (scores of 0–6) from the number of promoters (scores of 9 and 10).

- Divide that amount by the total responses.

- Multiply the final number by 100.

Number of promoters – number of detractors *100 = NPS Total responses

or:

% of promoters – % of detractors = NPS

Now, let's explain the promoters, passives, and detractors and their differences.

Promoters in NPS score calculation

A promoter is a respondent who gives your brand a score of 9 or 10 in an NPS survey, meaning they enjoy your product or service and would recommend it to friends.

Promoters – a score of 9-10 in Your NPS

Brand promoters are your superpower since they generate positive word of mouth. Once you get the NPS calculation, encourage promoters to write case studies and testimonials. Positive customer reviews increase sales by 18%, drive purchases, and make your brand immediately trustworthy. Use their power to aid decision-making and boost ROI.

Detractors in NPS Calculation

NPS surveys will help you determine the number of detractors.

NPS detractors are unhappy customers who give your product a score of 6 or below on the NPS survey. They are likely to discourage customers from using your products and will not contribute to the good word about your brand; you can expect them to complain, and they're likely to churn.

Detractors – a score of 0-6 in Your NPS

Detractors are your repair focus group, and you need to improve your relationship with them before they choose to leave. Ask them follow-up questions and try to enhance the experience according to what they say.

You can still turn them into promoters!

What are passives in NPS calculation?

Passives are survey responders who give your business a 7 or 8 in your NPS. They aren't happy or unhappy with your brand. Yet, it's important to improve customer relations with them to prevent them from becoming detractors.

Passives = a score of 7-8 in Your NPS

Consider passives important to your NPS because they could sway either way.

3 actionable methods to calculate Net Promoter Score

Now that you know how to calculate NPS let's look at the different methods for measuring NPS.

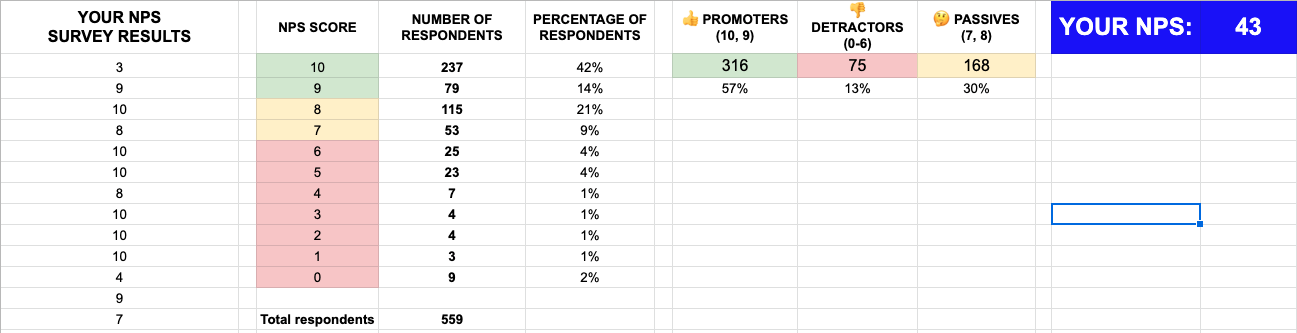

1. Calculate your NPS in Excel/Google Sheets

Use Excel or Google Sheets to calculate your NPS when you don't use software to automate it (Signup for Survicate to see how NPS works).

- Start with raw data collected from the NPS survey's scale-based question.

- Count the responses first—Add the number of replies given for each score.

- Group the responses—Determine the total number of answers each group provided (promoters, detractors, and passives).

- Calculate your NPS—Use the NPS calculation formula to subtract % detractors from % promoters.

- Divide by the total number of responses and multiply by 100.

Use the NPS calculation template we created just for you.

Insert the NPS survey results into column A, and the calculation happens immediately. Please make a copy of the NPS calculation template and use it when necessary.

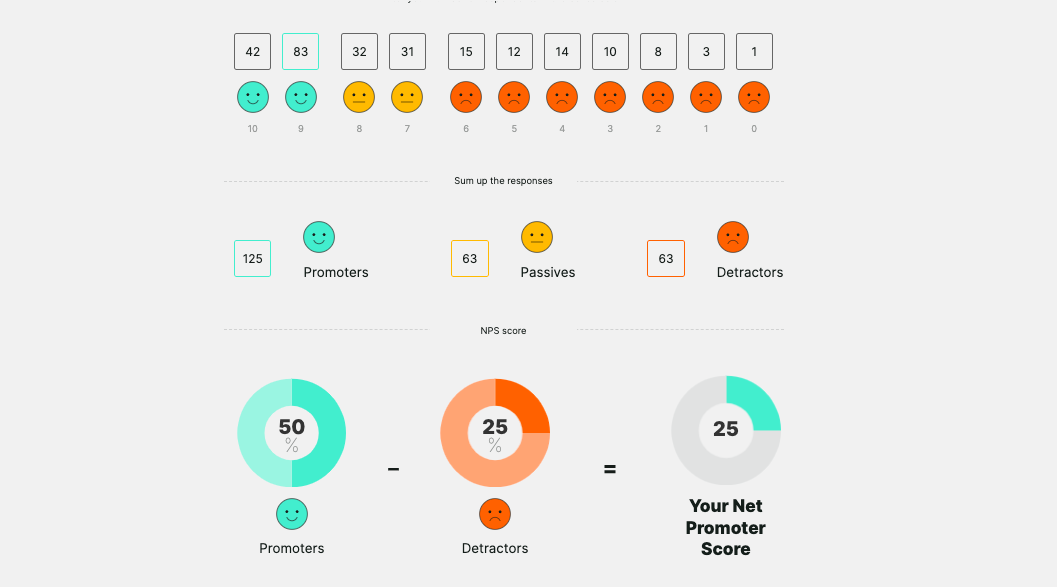

2. Calculate NPS with NPS calculator

For online NPS calculators, the steps are even easier. Input the results of your NPS survey into the NPS calculator, and from there, it will calculate your NPS.

Look at Survicate's NPS calculator example. As you can see, the NPS calculation is straightforward so that you can recreate the process later in Excel/Google Sheets.

3. Calculate Net Promoters Score with a survey tool

Launching an NPS survey with survey software such as Survicate is super quick.

Our platform runs NPS surveys with your customers and gathers the appropriate data. Later, you can check out your NPS score results in real-time through the Survey Analysis Dashboard.

Free NPS Survey Template

Survicate calculates NPS for you

The easiest among the 3 NPS calculation methods described above is to apply survey software such as Survicate.

The ready-to-use NPS survey template allows you to start your NPS campaign in no time and automatically calculates your NPS score.

However, if you need to collect feedback from thousands of users, you might want to check out our paid plans.

How many questions to ask in an NPS survey?

To get a reliable NPS result, only one question is necessary:

How likely are you to recommend our company to a friend or colleague?

Knowing your business's NPS score is the beginning of any NPS campaign. Once you calculate the NPS score, you need to understand the context around it, so support your NPS survey with follow-up questions.

What follow-up questions to ask in an NPS survey?

Follow up by asking open-ended questions. They will help you collect qualitative feedback and understand the reasoning. For example, for different customers, ask the following questions:

Detractors – “We're sorry to hear your response is so low. Would you mind telling us the reason you would not be likely to recommend our business to your friends and family?”

Neutrals – “Is there anything we could do to improve your score, making it a 9 or 10?”

Promoters – “We're glad to hear that you would recommend us to your friends and family! We'd love to find out the reason for your high score so that we can do even better.”

Pick the number to view the follow-up question:

💡 Apart from the NPS follow-up questions, our customer—Taxfix, asks three more questions that help in personalizing content that its app users receive. Getting to know the clients helps increasing in user retention and overall satisfaction which shows in Taxfix's NPS score—68.

Read the whole Taxfix customer story

Relationship vs. transactional NPS survey

There are two dimensions of surveys available to track customer happiness and customer loyalty. One is a relationship-based survey, and the other is transactional

- The relationship survey – evaluates the overall customer experience with your brand.

- The transactional survey – discovers the quality of a single interaction, such as the purchasing process.

Pro tip: Be careful about launching relationship NPS surveys after a specific event. Your customers confuse it with evaluating their recent experience (such as a transaction) instead of your entire brand. Surveying your customers at the wrong time could skew the results of your NPS scale

💡 Check out our template: NPS with follow up questions survey template

How many respondents should you survey?

There is no minimum or maximum number of respondents optimal for the NPS survey, unlike other surveys requiring a specific number of people to obtain an average. However, if you calculate NPS frequently, you will understand your customer loyalty/happiness. Think of it this way. Suppose you only have 10 respondents, and except for one detractor, they report as promoters.

In that case, you can still use NPS to

- Continue doing something right to increase customer happiness.

- Reveal where you may have gone wrong with your one unhappy customer.

Don't think that the one unhappy customer is just a fluke. The average consumer will tell 15 other people when they're unhappy with a product or customer service. In comparison, a happy customer will only tell about 6 others. Dissatisfied customers are more likely than not to respond to a rating survey, so it's essential to work on converting your detractors.

NPS survey channels

You can choose from various channels to distribute your NPS survey to your customers. Much of the decision depends on your specific audience and the method they would most likely rate you.

Email is usually a good choice because it's easy to embed the first question and direct your customers to your website to respond further. You can also distribute your NPS survey via in-app pop-ups or links sent via other communication channels (such as social media), your website, or

Test NPS survey

If using Survicate, a panel allows you to create your NPS survey in a few simple steps. Once your NPS survey is complete and ready for launch, generate a test link to send to friends to ensure its accuracy

You can even test it on other channels, such as your website, to create a mock NPS calculation. When you're happy with the process, you can distribute the NPS survey to your customers. You've finished your NPS calculation.

Now that you've discovered how to calculate your NPS score and have reached a final score, you're not quite finished yet.

- Compare your NPS score with industry NPS benchmarks, especially with your top competition. What is a good Net Promoter Score for your industry? How does your score compare? What are your competitors doing that may be impacting their score?

- Review the qualitative customer feedback you've collected as part of the follow-up process. Use open-ended questions and adjust them to where your customer falls on the NPS scale (detractors, neutrals, and promoters). Analyze your responses to gather important feedback you can now use to improve your NPS score.

- Create and share an NPS report to inspire action. Don't keep your NPS results to yourself. By sharing your NPS results with the team, you can work harder to increase the number of promoters. In addition, when your team becomes aware of feedback, they can work to improve these areas and any shortcomings as a personal goal.

Survicate lets you share access to the NPS analysis dashboard with all collaborators. Or you can download the NPS results into an Excel/XLS format. Be sure to present your results in a way that will make sense to all collaborators.

Summary

It's far easier to add more customers to your pool of loyalty if there aren't holes where unsatisfied users are escaping. Customer acquisition costs can hugely impact your bottom line. If it costs $75 to attract each new customer, you will need to have that customer spend $75 to break even.

Now, if you're focusing on improving customer happiness and loyalty, your profits continue to grow past that initial break-even purchase. Calculating NPS and applying its insights will impact the growth of your business in amazingly positive ways. Asking one question starts the conversation, and this is where the magic can happen.

NPS calculation will show how your company compares to your competition and where you need to focus your attention. Running a relationship NPS survey and following up with open-ended questions helps you understand why customers feel the way they do (positive or negative). And, from there, finding ways to improve is easier.

Ready to get started? Try our 10-day trial to test all Business plan features for free!

Read next:

- Get NPS Scores And Other Survey Responses in Intercom

- How to Launch a Successful Campaign in 6 Simple Steps

- NPS Complete Guide – Best Practices, Questions & Templates

.webp)